Interview with Losang Gyatso: The Spotlight Series Ep. 1

The Spotlight Series is a documentary series by The Yakpo Collective that highlights prominent Tibetan contemporary artists and their artworks. The series exist to provide resources for generations to come, in order to foster a learning environment based on art and creativity.

Tsering Zangmo: I wanted to start off with some icebreakers: what is your favorite flower?

Losang Gyatso: Oh my god, I have a garden. I like, I really don’t know the names of too many flowers, but I like wildflowers, perennial wildflowers more than big blooming annuals.

T: Okay, and how are your dance movies?

L: Excellent.

T: Excellent, I see

L: I keep it in shape. Daily practice.

T: Can you tell me a little bit about what you do and your background?

L: What I do these days, I stopped working. I’m sort of retired. So I primarily try to paint and read, and am involved in small projects. My background is I was born in Tibet, in Lhasa, and we left Tibet late ‘50s during the occupation and I lived mainly a couple years in India, but early schooling in Britain and most of the time here in the US since 1974.

T: I was looking at your portfolio, I see that you are not only a painter but also an actor! Lord Chamberlain.

L: Lord Chamberlain, Phala yes. That was an incredible opportunity, wonderful experience. None of us Tibetans, who took part in that project were really trained actors, so it was really a learning experience but also a very very emotional experience for us also, especially the people even older than myself who were there as extras playing in the background. They were getting very emotional during some of these scenes. Especially the 59 march in Lhasa. A lot of people actually broke down and it was incredible.

T: Can you tell us about the project, and also how you got involved with it?

L: Well the project was based on a book written by Melissa Mathison, for people who may not know her, she was the late Melissa Mathison. She was the wife of Harrison Ford, the actor, and she wrote the book and she took it to Martin Scorsese and I’m not sure why she took it to Martin Scorsese as opposed to other directors. I think primarily because he’s dealt with these issues of spiritual conflict. He’d done a movie on Jesus Christ, so I think Martin Scorsese was someone who’d spent a lot of time thinking about the spiritual conflict of individuals and dealing with issues and things that really tear people apart and how people deal with it from the spiritual perspective. So I think, that’s one of the reasons why she took it to him. He had made the decision to cast real Tibetans and then I think he realized that there were no real Tibetan actors, especially at the time, this was in 1997, so he casted for people that he thought would fit the roles, and I was lucky enough to be chosen to get that part. So that’s how that happened. Filming was done in Morocco, we were in Morocco for 3 months. Incredible sets built right there in this completely out of the way place in Morocco. Pieces of Potala Palace, pieces of different Tibetan scenery all built, lots of interiors all built there.

T: That sounds like an amazing experience. Speaking of your background, I hear you grew up during the era of the Beatles, the Moonlanding, Vietnam. How did that shape you and how did that stand out?

L: I think, I haven’t really thought about it, now that you ask, how it treated me. I was a child in the ‘60s, so I missed out on a lot of the fun of the ‘60s, having been just a kid, but I think it’s difficult to say how a period shapes you, because it depends on your environment and your immediate people around you and their political and emotional state. For me, I think it’s made me have a more liberal view on things, a little suspicious of people who follow extreme thinking, and so I’ve learned to kind of take things into consideration in a way that is more accepting than perhaps some people are I think, and some has to do with the movies and the music and the books that were coming out at the time, generally. Not in the Trump camp, is what I mean.

T: Moving back to your work, what does art mean to you?

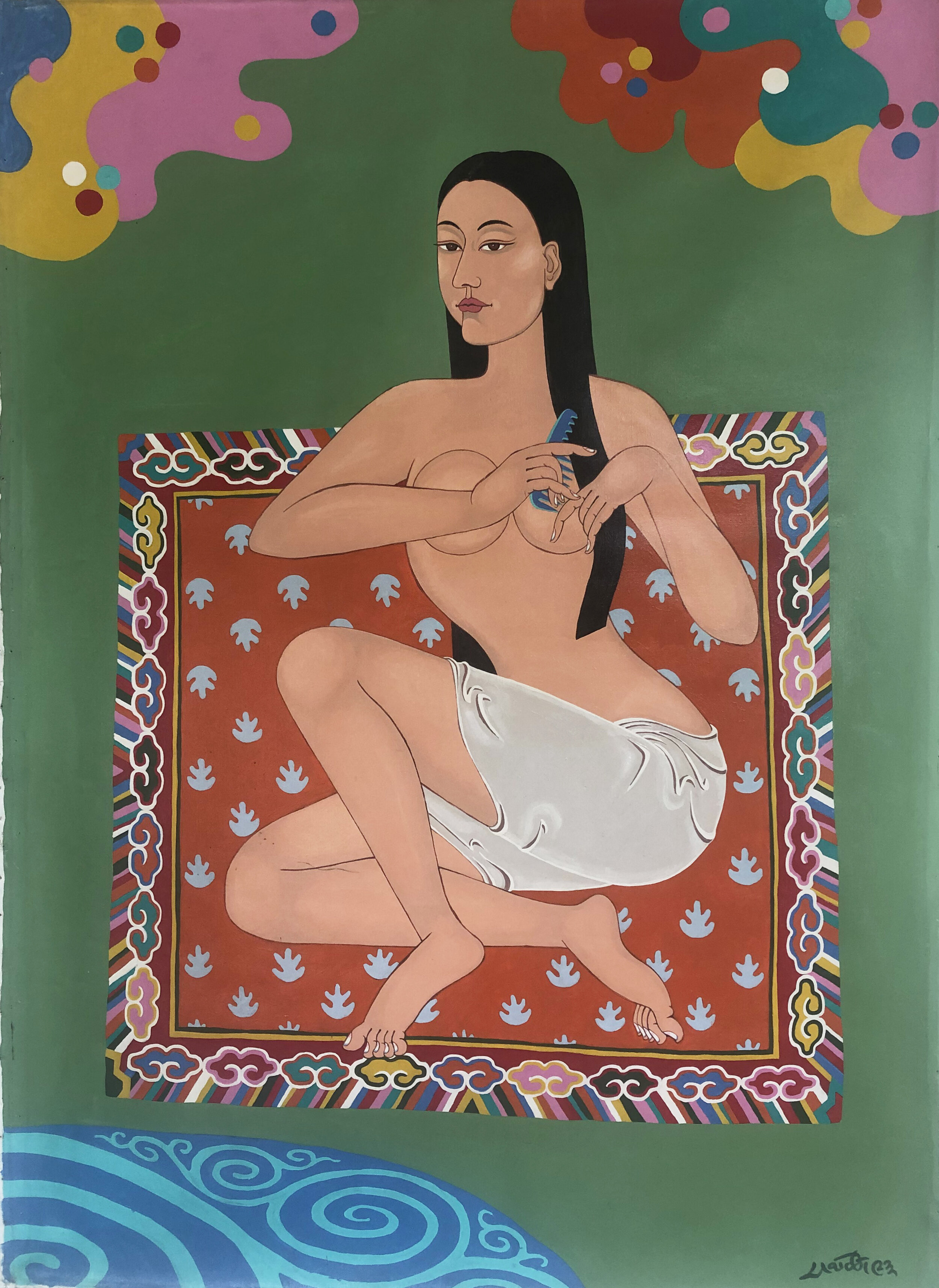

L: I think on a very fundamental level for me, art means a way of seeing things, from morning to night, how you see things. I think you can see things artfully and be aware of everything or you can not see anything and just walk through life. So generally speaking, I think it’s an enhanced way of receiving the world visually. I don’t mean to sound convoluted, but I think that’s fundamental, for me. In terms of my own artwork, it really was kind of a way, I’ve always kind of drawn and liked visual imagery, but for me it was, when I started to paint on an actual canvas in the early ‘90s I was really aware to try and create a piece of art that’s Tibetan in some ways, not necessarily a replica of a traditional Tibetan painting, but Tibetan nevertheless, conceptually that I could have in the apartment. I used to live in New York City in the late ‘70s, ‘80s, ‘90s, and I had a small apartment in the East Village, lower east side. There was nothing on the wall that was actually Tibetan, I didn’t want Thangkas all over the place, so I created a painting of a Tibetan Bather. A lot of museums in New York you always see Bather. Bather is almost a cliché subject in the art world. You have paintings of Bathers from Spain and France and Italy and everywhere, but there were no Tibetans. And yet Tibetans were great bathers, right? Hot springs all over Tibet, people would go on pilgrimage and spend time in the baths and enjoy the water and the spring and eat and there were no paintings, so I created one. It was a way to have something Tibetan on my wall. I didn’t want to pretend to be a religious person by having Thangkas everywhere, so I created this painting. So it was a way of reconnecting with myself, with my past.

T: In case the people at home aren’t familiar with-

L: Shall I tell you a little bit about the painting?

T: Yes

L: So the painting-the title is not important, it’s just called “The Bather”-the painting is interesting because when I decided to paint something, the subject matter-Okay, so I said, I want to paint a bather, a Tibetan bather, as opposed to bathers from other cultures. And that led me to: how do you do that? Do I try to paint a realistic painting of a Tibetan woman taking a bath? But then you get into styles of artwork: realism or impressionism or etcetera, etcetera, which is not Tibetan, but I didn’t want to paint her in a Thangka style, not that I could necessarily, so I looked to Tibetan material culture and so in this painting, the cloud formation and the carpet she’s sitting on goes back to Tibetan weaving styles, carpets and weavings, etcetera. And the style of the body is painted with a strong emphasis on linear line work, like in Thangka painting. So for instance, the perspective, the carpet is not in western perspective, infinity perspective, which seems very un-Tibetan if you look at Tibetan paintings, old Thangkas, or you look at the houses, tables, things that have angles, there not in perspective, in renaissance style of perspective. They are in the perspective you see what you want to see. So what looms large for you, is what’s interesting to yourself. So for instance, the carpet is completely flat because I want to see the Tibetan carpet, I don’t want to see it in perspective, disappearing into the distance. So that was my way of not only choosing a subject that was Tibetan, but of trying to build some conceptual underpinnings of Tibetan thinking, world view, and art.

T: Was there an important moment when you decided to follow your path as an artist?

L: No, I don’t think so. There wasn’t any kind of breakthrough, or anything like that. After doing that first painting in ‘93, I kind of wanted to do more, but things happened in life. I moved to the west coast, I got busy, and a lot of time went by. It wasn’t until about 10 years later, when I left NYC and moved to Colorado, in Boulder, and I made time to create paintings. I decided to do it properly, instead of just painting a bather, I decided to see what I can explore and I was very interested in tracing Tibetan identity back to prehistoric times. We know Tibetan art and Tibetan history, but Tibetan history basically stops at Nyatri Tsenpo, the first king, about which we really don’t know that much. Beyond that, 2000, 3000, 4000 years ago, we know very little. So I am interested in prehistoric Tibetan art petroglyphs and petrographs that you see in Ngari, Toe Ngari and certain northern areas of Tibet that still exist, and because of the climate in Tibet these rock paintings are still very vivid and in good shape. So a lot of that is rituals and hunting scenes and animals, and very very beautiful and interesting, and you can see, even back then, before Thangka paintings, before all of that, the people had a tremendous ability to express visually things that were important to them and vivid to them around them, their lives. What’s actually very interesting is that some of these petroglyphs, rock art, have been found in areas of Tibet that are today very very arid and there aren’t really settlements in that area. So, 4 or 5000 years ago, in those areas of Tibet, the climate was very different. There were trees there, you can see it in paintings on the rocks, people dancing around trees, but there are no trees today. So it’s very interesting, it gives us a glimpse into how people settled, what was important to them, how they developed society, and the kinds of spirits for them, formed the beginnings of Tibetan spirituality. And Bonpo right, they were all Bonpos at the time.

T: What does contemporary art mean to you?

L: I don’t really dwell on that, what that means. For me, it means creating something relevant to people today, primarily, and I create art for myself, which means I create art for somebody who is Tibetan, primarily. And I think it’s very important, who you create art for. Don’t create art for a market or for other people. It’s difficult to create art for Tibetans generally, because most Tibetans are not used to participating in art, so there are very few Tibetan museums or opportunities to see Tibetan art. There are few Tibetan artists, so it’s a bit of a challenge, but I think in the long run, creating art that connects with people that have a background like yourself is probably the way to remain truest, when creating art.

T: I was a little surprised about your answer about modern art, because when I was doing some research, I saw that before you said the significance of modern art in these times is that it can be a voice, not just for people outside of Tibet, but we also have to be mindful of people inside Tibet too.

L: In the early 2000s, I had a few friends starting their small nonprofit, called Mechak gallery. It was just an online project to try and unite Tibetan artists, contemporary Tibetan artists. Because they are all over the world, people practicing in Australia to London and etcetera, and also primarily Lhasa. There is a very strong group of Tibetans practicing art. A lot of them are a part of this collective called the Gendun Choephel in Lhasa. So, the idea of Mechak at the time was to try and be a platform, kind of similar to Yakpo, where we can see online what people are doing, wherever they may be, and we were even able to get a couple physical shows, one at the university of Colorado in Boulder put on a show called “Waves on the Turquoise Lake.” We brought out some artists from Tibet as well as Gonkar Gyatso from London and Karma Phuntsok from Australia etcetera, and it was a fantastic show.

T: Does your identity influence your work in any way?

L: I don’t think one would be able to create any work that isn’t influenced by their identity, that’s a given I think. I don’t try necessarily to create work to express identity, but I think it’s natural, no matter what you do, right? So I think so, yes. And being an older Tibetan myself, I think I bring perspective. That's...you know when you say identity, there are so many identities, even for Tibetans, there are so many identities. And I’ve seen over the decades, Tibetans are changing, as all people are changing. I mean the English aren’t the same people they were in the ‘60s, the French, the Americans are not, etcetera. But Tibetans are changing, not only from change of technology and perspective, but are actually changing in different ways in different places. Tibetans are certainly not what they were in the 1940s, 1950s, Tibetans in Tibet are changing, Tibetans in India and the US are changing, and everyone is changing. So my interest really is, with all this change, what, in terms of identity, what is Tibetan identity? And how can we define or express and experience Tibetan identity, being, not the people we were 60 years ago? So, that is my main interest is that, in terms of looking at art or my own work. To see what parts of Tibetan identity are important enough and portable enough to carry forward and what parts are weighing us down that need to be let go of, because trying to carry everything forward is a losing proposition. So distillation and trying to understand what makes us “us” and what we can carry forward, that is my interest.

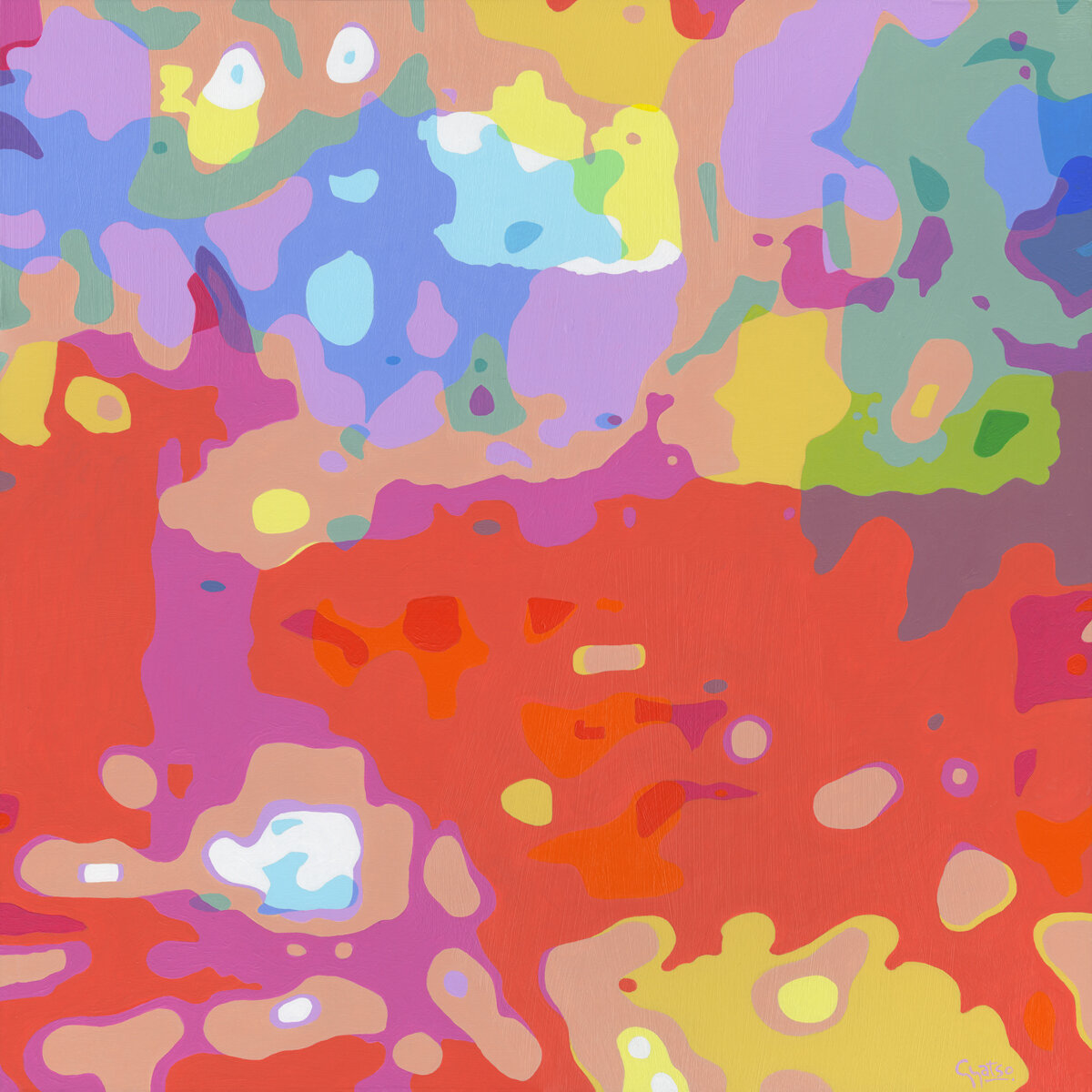

T: What are your favorite parts or details from your artworks and why?

L: They’ve changed over the years, obviously. In artwork I was doing in the ‘90s or early 2000s, I was very very interested in making relevant things that were old, from petroglyphs and petrographs made by Tibetans 5000 years ago to even Thangka paintings, because all of us have Thangka paintings, like the one there behind you, but my sense, and maybe it's just me cause I grew up in the West, I think Tibetans haveThangka paintings and revere them and put them up, but they rarely actually look at them, up close, every square inch. It’s obviously an object of worship and reverence but not an object of visual stimulation and appreciation. So I was after the prehistoric Tibetan artwork that I was trying to get close to, and trying to get close to Thangkas, and some paintings, Jetsun Dolma, for instance, and the Mahasiddha Virupa, and trying to really imagine them and represent them in a way that you can actually look at them, up close, and get close to them. Because normal Thangka painting has so much going on, so many details, that it’s hard to actually get close to Jetsun Dolma herself, and her energy and compassion. So I’ve been trying to get close to Tibetan art over the ages, and found that these days, in these last few years, getting closer to the actual concept of what makes Tibetans Tibetan but without using any visual cues or precedence in Tibetan art, so in the last few years been doing more abstract work. But abstract work with ideas and, this sounds kind of arrogant to say, but trying to express in my own way, what Kundun has been saying over and over again: the important thing in life is for people to achieve happiness of some kind, and that is the basic premise of Buddhism, to minimize suffering and to increase happiness, which led me to thinking, you know, we got political situation in Tibet being so dire, and situation in exile being so spread out and becoming more diluted in many ways, that when I look back at my generation; Life in Tibet, even in Free Tibet, wasn’t easy, living on the Plateau, thousands of years, very difficult. But we had really fashioned, over the centuries, an understanding of happiness, of being content and happy, that is, I think, unparalleled in the world, and that combined with Kundun’s message of happiness. For me, I’m thinking something that we’re losing in the last 30, 40, 50 years, is our connection to this, and that we’ve becoming so mild and beaten down by politics and by Chinese atrocities and Chinese accesses and our lives in exile, and I think it’s very important for us to reconnect with who we are. The project of Tibet in the last 600 years, the last 1000 years has been to grow happiness and to understand suffering and happiness. So that’s primarily what I’m trying to do in my series of work just called Happiness, is achieve a glimpse of that. (Tibetan stuff). I’m doing very “high-minded” things, but that is in my own way what I’m trying to do.

T: Right, in your Happiness series, you say it’s like a correlation of happiness with the ideas of change and interconnectedness. Going back to what I said earlier about Tibetans inside and outside of Tibet, do you think that the art movement has increased interconnectedness for inside and outside Tibetans?

L: Absolutely, absolutely. I think that the art movement, and the music movement and the film movement to a degree-all of this is unbelievable. The art movement starting from Lhasa and then out in exile, it’s really clear, it’s gone under the radar and connected people. And you have to be plugged in. If you're not plugged in, you're not connected to it, it really doesn’t affect you. But if you're plugged in to what Tibetan artists are doing, Tibetan contemporary artists, Tibetan contemporary musicians, poets, literature, song-it’s an unbelievable bridge-building process that’s going on. It’s very very exciting and I think it’s a way to, not only connect in a superficial way, but it’s for us that we are, inside Tibet and outside Tibet, we are absolutely completely the same. We are going through the same suffering, not so much politically, obviously, we are not going through the same political pressure and force that people inside Tibet are, but we are going through the pressure of being Tibetan today and trying to maintain ourselves and maintain our autonomy, maintain our independence philosophically and psychologically. So that’s why I think arts can really be a part in maintaining growing and understanding of independence and it’s crucial for this to continue and for people to become more interested in these things.

T: I loved what you said before, about the arts. It is making a viable space for creative long-lasting solutions, and through your work, such as the Happiness series, you can suddenly put in a message or teachings.

L: I’m certainly not saying that I’m some kind of highly-achieved practitioner of Buddhism or anything like that, but my interest is in Tibetan culture and when you read about Buddhist philosophy and psychology, the things in Tibetan culture that have led for Tibetans to be a people that laughs a lot and can take a lot in stride, and enjoy each other’s company, and the lightness-there’s a lightness to Tibetan culture that we have to maintain. Because it’s very easy for us to become bogged down, as we become more British and more French and more Indian and more Chinese, it is very easy to become heavier, and I think it’s such a shame for us to lose our lightness. So happiness, when people think I’m painting pretty pictures of flowers and things of happiness-I’m not. I’m talking about the essential understanding, that I think all Tibetans, and I’m not just saying high lamas or high Geshes or high Yogi practitioners. The average Tibetan in Tibet, for hundreds of years, it’s seeped down to them. It seeps down to the average Tibetans across Tibet for centuries that change is inevitable, change is constant, impermanence is a state of fact and that kindness and compassion tend to lead toward a happier state of mind. I mean, these are very fundamental things, which basically evolved us psychologically into happier people, happier than most people, this sounds chauvinistic, but I think happier than most people in most societies. And I think this is our biggest fear, after politically losing Tibet, my biggest fear, is actually losing that lightness and that characteristic we have, which is what I’m trying to imbue in these paintings. And at the start of the project, it’s not like “because of this do that,” it’s one of those paintings that reminds people, gives them a glimpse of a way of seeing life that’s connected, of life that’s changing, of life that has all kinds of monsters, and is essentially happy, in a way, in the long-view and perspective.

T: Our most intense experiences usually drive us, and drive the art. Do you have any memories or challenges that led to the blooming of the Happiness Series?

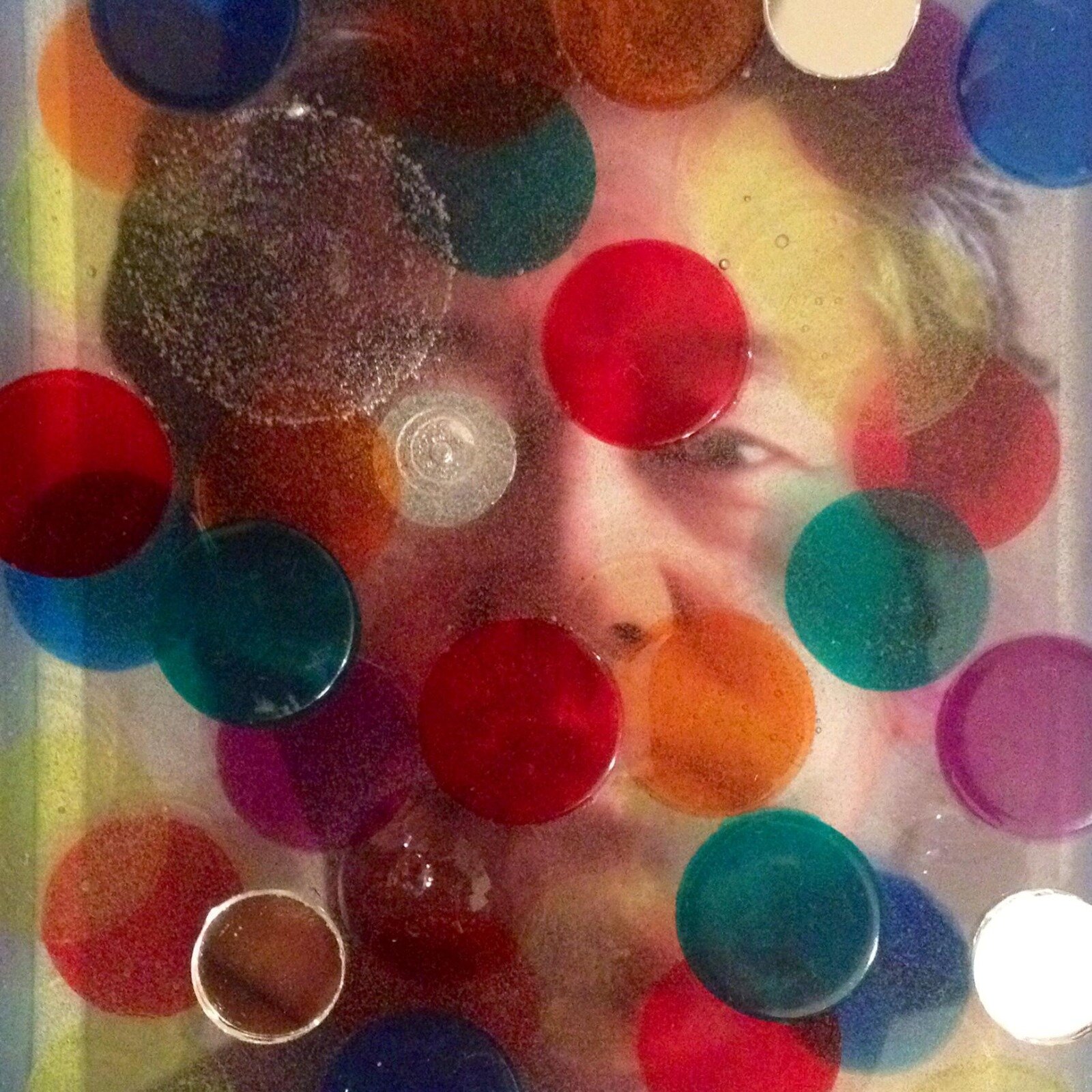

L: The Happiness Series in particular came to be by accident. I was always interested in photography and, not necessarily carefully composed and configured photography, but photography of things happening, on the subway, on the trains, on the street, etcetera. Having worked in advertising, I was really interested in how photography can be such a powerful way of capturing-the whole job of advertising was to seduce people with products and services, but photography and film was used to capture moments and images that connected with people and somehow brought up feelings that were related to a product. Then I played with photography in photoshop and different software to make, to try and get to the essence of an image, rather than just the skin. So this particular series of paintings started with photography and digital manipulation and then painting, because only with painting could I fully control all the colors and all the parameters of what goes on canvas. Maybe it’s because I’m not very good with computers and manipulation, but that’s how that happened.

T: So what are some challenges you face when you’re creating your artwork?

L: Laziness, procrastination-the biggest challenge is I’m realizing that people who have productive creative lives have been very disciplined with their time and many times created routines for themselves, which has been a challenge for me. Once I’m in the studio, once I’m in the environment, I can work, but it’s getting my a** into the studio that’s the problem.

T: Which of the three artworks is your favorite and why?

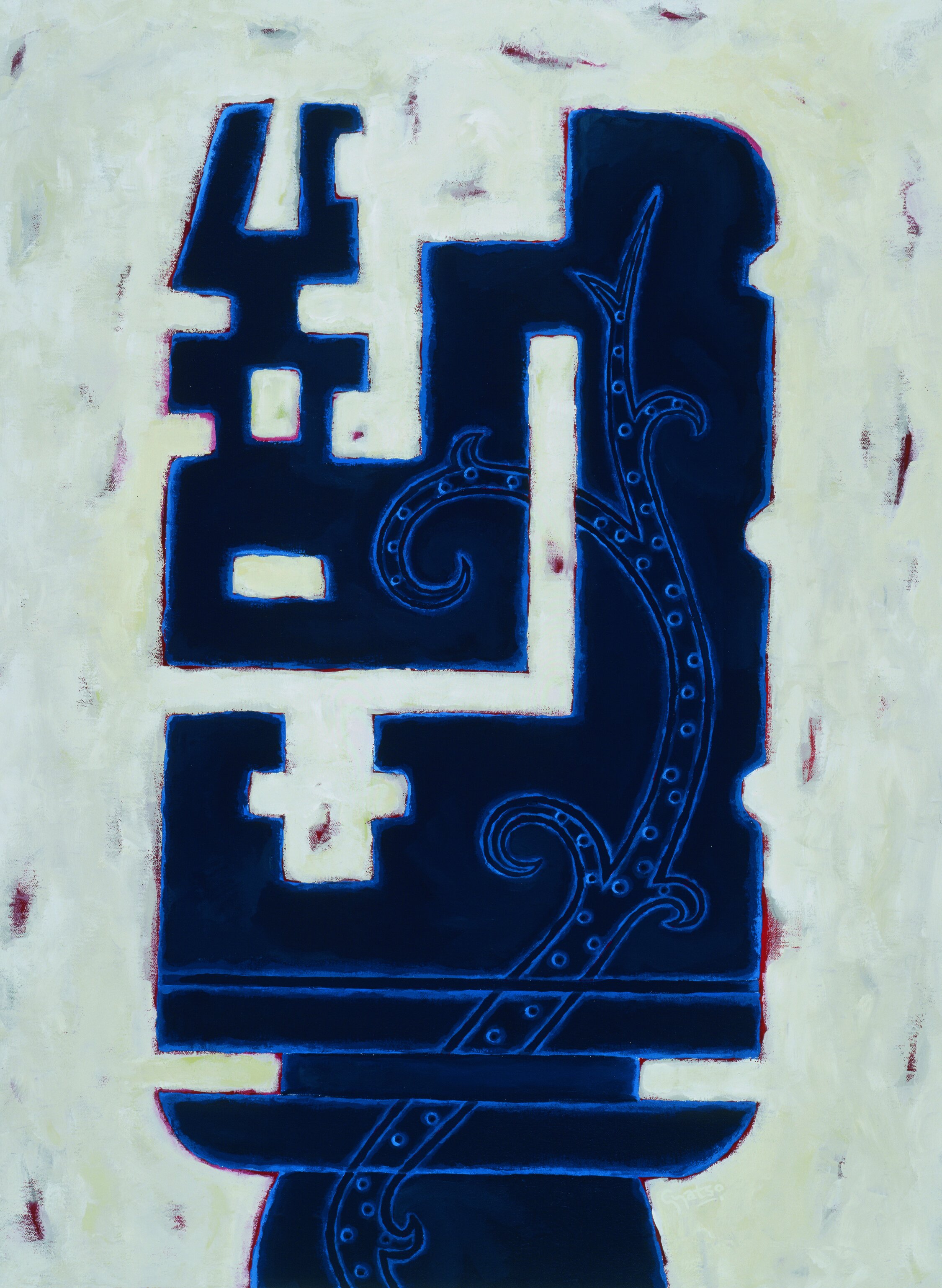

L: Oh, well I haven’t talked about the Key, right? One of the three artworks you're discussing is called the Key. That is basically a large painting of a Tibetan key and that was made around 2005. I was interested in the power and nature of Tibetan material culture because everything that was made in Tibet, craft, artwork, buildings, weavings, shovels, plates, and cups, all of it was amazing. It was the entire process, from finding the materials, whether it was from mining, to timber to wood, all of it was sourced inside Tibet. So an object like a key, lock and a key, was made by a blacksmith and was crafted to create this individual lock with a set of keys. Each lock and key is unique, but the materials, where the metals were mined, etcetera, all of it tells a story of the society and the time. So you understand a key, where it’s made, how it’s made, where it’s from, etcetera. I was so fascinated at the time in that, so that was my favorite painting for many many years. Obviously your question, I have to say the latest work is my favorite, so at this point, I’m most excited for the Happiness Series

T: Why?

L: Because i think each painting was one-off, I was interesting in something, I created a painting, and then it’s over and finished, but the Happiness Series, I can see it can go on and on and on, I have to put a stop to it, eventually, I have to decide I’m going to do 10 of these or 20, because it’s probably possible to do a 1000 of these. In that way, I think it’s also my laziness coming into play-this can go on and on without too much effort. But also it’s a very calming and pleasant place for me to do these paintings, many times I create them digitally and then I change parts of it and my next challenge with this series is to change the color palette back to traditional Tibetan colors. So that you’ll have a line of work and shapes and forms based on photography and digital manipulation with a changed color palette back to traditional Tibetan colors in paintings and weaving, which means mineral colors, so I’m looking forward to that.

T: Like, seeing the pattern of organic colors. So how do you overcome the artists blocks you’ve spoken of and do you have tips for young artists or people who are beginning when they have artist blocks?

L: I think the best way to overcome any kind of creative block is to go and see things, go to museums, read books, not just on art, any book. The more going in gives you much more resources for things to come out. And for Tibetans, obviously it’s taking in world culture but to take in Tibetan culture, read Tibetan history, anything! People say “oh, to create art you need to take art,” no, you can study Tibetan agriculture, Tibetan architecture, Tibetan history, Tibetan weaving, etcetera, all of it becomes a soup and it can come out in ways. I think that’s the creative process, you need to be very well stocked to put out things. I tell young Tibetans entering art, writing, film-making, to read, talk to older Tibetans, talk to Popo-La and Momo-La how they felt about things, what they liked, what they didn’t like, what they’re excited about, what interested them when they were young, what is beautiful to them, what is ugly to them; all of these are interesting things.

T: Is there anything from your work that you want people to take away from?

L: One thing I want from people is something that most artists don’t get; even the most famous artworks. The average amount of time people walking through a museum spend about 10, 15, 20 seconds then move on. Even in front of a painting that is considered a masterpiece (I’m not saying my work is, in any way), but even in front of the Mona Lisa. So, my wish is that, probably that of any modern painter, is that you spend at least 50 seconds.

T: In the Happiness Series, I see there is a theme of colors-in your other artwork too, there is an element of multicolor touches, these organic colors, including the Bather and the Happiness Series. Can you tell us more about this theme?

L: I think it really goes back to my love of Tibetan weaving and paintings, or if you look at Tibetan carpets, I mean it’s colorful. And what’s beautiful about the color of Thangka paintings, as well as traditional weaving, is all of the colors were sourced from minerals and plants inside Tibet, and the colors are extremely beautiful. With synthetic colors, certain colors become extremely dissident next to each other. Whereas natural colors, plant and mineral colors, you can just look at the way of the Tibetan Pangden, how the colors are combined and sit next to each other-even colors that are not complementary, colors that are very different, like green and orange, look extremely beautiful next to each other, they enhance each other. There’s very little dissidence. Also you have to remember, in the vast landscapes of Tibet, a lot of Tibet is quite barren, very beige and gray. To see someone wearing an apron like that, or to see a Thangka painting is just exquisite contrast. That’s why I’ve always loved the Tibetan colors. Also the Tibetan color palette is very different. Different societies and cultures have different palettes, right? I mean the Indian palette is very different from Tibet, the Chinese palette is very different from the Tibetan palette. There are colors and combinations of colors used in Tibetan folk art, weaving, paintings that are unique and exquisitely different. So it’s all of these things, when they vibrate together, Tibetan colors, the scheme, when they vibrate together it creates a Tibetan environment. That’s something I’ve always been interested in looking at.

T: We talked earlier about the hanging thangkas. It’s not for decoration, it’s an object of devotion and Tibetan thangkas are sort of a bodily support, visual support to help you transcend when you’re praying or something like that, it will help you visualize.

L: Thangka paintings are an exquisite form of art and it is an integral part, because we have such huge pantheon of deities and buddhas and lamas, etcetera, the subject matter is vast, so not only is it record keeping, but are extremely important tools to help you visualize as you practice. But I think also, from an artistic standpoint, young Tibetans should realize that Thangka paintings are not just one-off monolithic styles of art, and that thangka paintings have changed and evolved over the centuries. It is very interesting how the changes have occurred, because only in Tibet can this kind of thing happen because the artwork itself is transportable, it can be rolled up and taken, taken for oneself and moved across Tibet, giving off influences from people and artists in other areas. And the artists themselves were also highly transient; many artists would be famous artists from Lhasa commissioned to work in other places, and people absorb the artwork and art from that area. It is very interesting, not only outside influences, but influences within Tibet itself, how the styles have changed.

T: It makes me think about how we were talking earlier about the Happiness and the interconnectedness, the idea of that, thinking back to when people were making classical artwork, people couldn’t see it if they weren’t in front of it, but contemporary artwork can be digitized and shared.

T: Do you have a daily routine? And how does it enhance your creativity?

L: My daily routine that I try to keep, not successfully everyday, is to have a simple breakfast first thing in the morning. And then I try to catch up a little on the news, about 10 or 15 minutes, just to make sure I didn’t miss anything last night. Then I try to either read or go to the Studio, or I’ll procrastinate by doing some chores around the house or running errands, but primarily that’s what I’ll try to do. And if I do make it to the studio, then it’s much easier, just continuing what I’m working on or creating something new, yeah.

T: What’s your favorite thing to do when you’re not working on Art?

L: Walking, exercising, working physically. We have a small backyard I’m always trying to reconfigure. My wife will have an idea how to do this and then it’s my job to go do it, which takes a lot of muscle and time, so I enjoy that!

T: You said earlier that you have a garden. Does being in the garden ever enhance your creativity?

L: I don’t think so, it just gives you fresh air!

T: What is your most treasured tool or something you can’t live without?

L: I was going to say my cellphone, but that’s so...bizarre of a thing to say. No, I don’t really have a single object that’s that important. I have many objects that I love though. Years and years ago, I started collecting Tibetan material culture. Tibetan stuff, made in Tibet. On my first trip back to India from living in England for 10 years, in the early ‘70s, I used all of my savings at the time to buy a small knife from Tibet House in New Delhi. It was extremely expensive at the time, at least to me, and that has led to me, over the years, collecting Tibetan knives, Tibetan weaving, Tibetan mechak, and these things enrich my life. So when you ask me if I have a favorite object, I don’t necessarily have a favorite object, but I have all of these objects, and they all really help fuel my visualization of things for paintings, for work, etcetera.

T: Is there a specific style you want to be remembered for?

L: No, not really. I think my effort to try and capture and develop the use of color in visual work is something I’m proud of. I’ll tell you a small story: if you look at antique Tibetan carpets from the 1950s, different styles of carpets from different parts of Tibet, color palettes are different but they are exquisite. Every single palette and combination of colors, they are exquisite. They tell a story about that area and even the environment, the palette of colors in certain carpets kind of give you a clue as to the color palette of the environment people were living in at the time. So, when the carpet industry in Nepal took off in the ‘60s and ‘70s, one of the biggest markets for Tibetan carpets in Nepal, export markets, was Germany. And then Germans and the German market said they like things muted, they don’t like such bright colors, carpets in the dining room should be muted. And the Tibetan carpet industry in Nepal started making these horrible, muted color Tibetan carpets. I mean, it was like a crime. So, my pet project is to work against that kind of criminality against Tibetan aesthetics; we need to keep and maintain and develop the appreciation of the color palette and designs that really create the DNA of Tibetan culture. So we must never do that, we must never make things toned down for other people. If things do tone down, it has to be of our own volition, by our own need and by our taste, not for other people.

T: What advice do you have for young artists?

L: I don’t think artists need to do anything particular, any particular style or message, other than what they feel closest to their heart and to their passion. The main thing is to, I think, read and gather information from Tibetans, from older Tibetans, about anything. I think you need to be curious about everything, not just about art. Be curious about all aspects of life. How we die, how we’re born, how we marry, how we farm, how we make things, how we fight, all things are important to understanding, all of it. To be an artist or writer, you need to actually have as much ammunition as possible, and nutrition. And for artwork, you need to have a lot of information for anything to come out of you. And read, read a lot about life in general, but also life in Tibet in particular.

T: What are your thoughts on platforms like Yakpo?

L: My thoughts about platforms like Yakpo, and I’ve noticed them in recent years, is they’re absolutely fantastic. Young people should know that 15, 20, 30 year ago, they were non-existent, platforms like this. So for Tibetan artists, thinkers, writers, creatives, it was completely analog and it was hard work. It was so difficult to be in touch and keep in touch, so I think platforms like Yakpo, where Tibetans-it’s a process of, not only of understanding and comprehension, but also comparing notes amongst and between Tibetans that is critically important. It’s a learning process. And for us to know, not only how we exist where we are, but how they’re experiencing things and existing around the world, in Tibet, especially in Tibet. And as I said earlier, in very simple ways, we need to understand what is pretty to us and what is ugly to us; what is frightening to us and what is attractive to us. And all of these things so we can share, as we grow up in different parts of the world and inside Tibet and outside, so we can all maintain Tibetan culture in this very kind of organic and instantaneous way, I think it’s fantastic. Thank you to all of you, for doing that.